Public consultations in Switzerland, a country with 144 years of experience in its implementation, offer Swiss citizens the opportunity to actively participate in the country’s political life. This, through three instruments: the popular initiative, the optional referendum, and the mandatory referendum [1]. With the first instrument, citizens can present proposals to modify the law; the second demands that a law has to be submitted to a popular vote; and with the third, each amendment to the constitution is submitted to a vote of the people.

Regarding Mexico, after the recent survey carried out to decide the destination of Mexico City’s new International Airport (NAICM), it could be said that the instrument most comparable to Switzerland is that of a popular initiative. It should be noted that, in Mexico, from 1977 to 2014 efforts have been highlighted to implement a process of transition and promotion of a democratic political culture, which recently originated the use of instruments of direct democracy, which are implemented under constitutionally established processes. As it is well mentioned in Article 35 of the Supreme Law of Mexico: “Popular consultations on issues of national importance will be subject to: 1) being called by the Congress of the Union, at the request of 1) the President of the Republic; 2) the equivalent of 33% of the members of any of the Chambers of the Congress of the Union; or 3) citizens, equivalent to 2% of those registered on the nominal list of voters” [2]. In addition, that petition must be approved by the majority of each Chamber of the Congress of the Union. However, the occasions on which they have been carried out are almost null or are used in specific cases to integrate national development plans.

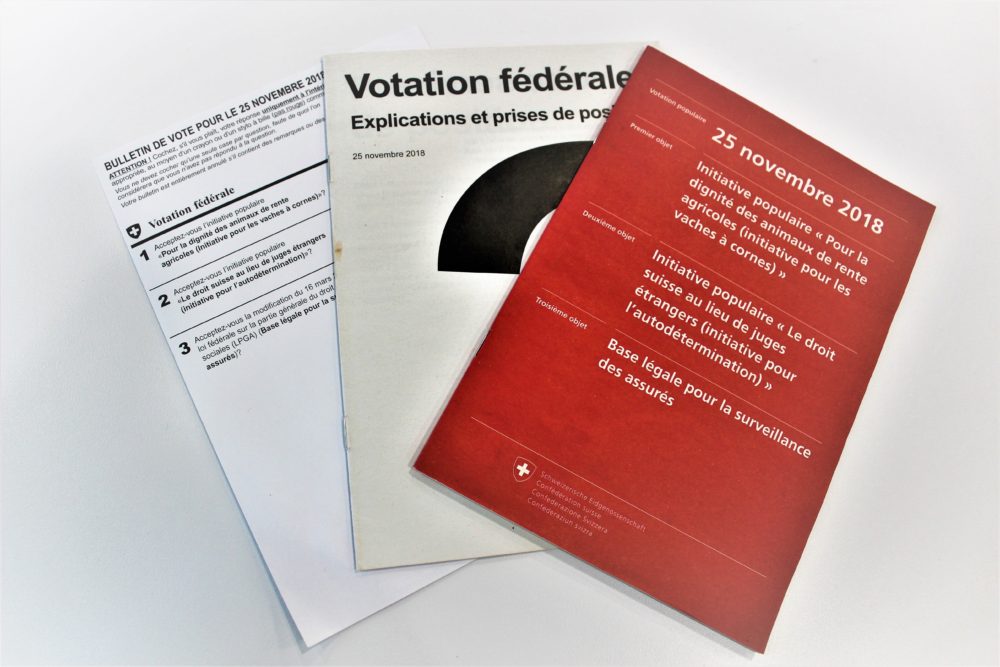

For popular voting in Switzerland, a citizen is called to the polls 4 times a year to debate on some 10 issues. In fact, “since 2000, more than 150 different issues have been the subject of national popular voting” [3]. The way to inform citizens about the issues is also very organized. Two documents are delivered to each voter: the first is that of explanations and positions taken by the parties; and the second contains the description of the topics that are voted on; this description is presented summarized, in detail, with arguments with the text put to the vote; and with recommendations from the Federal Council and the Swiss Parliament. On the contrary, in the “citizen survey” carried out a few weeks ago in Mexico, there was a lack of clear statements, a context and decision-making; causing a low percentage of the population to vote, and without sufficient information on the projects (technical studies, feasibility, total investment, benefits, among others).

That is why, in Mexico, the institutionalization of consultations is imperative: Mexico’s Supreme Court of Justice must decide on the constitutionality of consultations; while the National Electoral Institute will be in charge of organizing, developing, computing and declaring the results of the public consultations in question. Specifically, there is the Federal Law for Popular Consultation, which regulates Article 35 mentioned above and which “aims to regulate the procedure for convening, organizing, developing, calculating and declaring the results of popular consultation and promoting citizen participation in popular consultations ”[4]. This institutionalization responds directly to the need for consultations to be organized, and allow a vote with real counts and without disturbances; and that, at the end, they allow the most appropriate decisions to be made for the future of the country.

Finally, and in comparison with the process established in Switzerland, it would be more appropriate to name the participation that was given for the approval or cancellation of the NAICM as a “popular survey”. It is important to remember that the consultations are carried out to know the points of view on those citizens who have vast information on the issues, and that these opinions support accountability, for example: the system, government, transportation, social services, environmental issues and healthcare [5]. When citizen consultations can derive from the population, criteria must be established for the approval or cancellation of certain issues, taking into account, number of voters, signatures collected, and deadlines to obtain the signatures.

It is essential to raise and spread the need to rely on the Swiss standard in direct democracy; in addition to making a call to citizens to inform themselves on the issues subject to popular vote. Making informed decisions will create a truer social, economic and political environment. For now, we should be aware of the way in which public consultation is handled on issues such as the construction of the Maya Train, oil refineries and the Tehuantepec Isthmus Railroad.

[1] Presencia Suiza (s/f), Confederación Suiza. Democracia Directa. Consultado en: https://www.eda.admin.ch/aboutswitzerland/es/home/politik/uebersicht/direkte-demokratie.html

[2] Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión (2018). Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Consultado en: http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/1_270818.pdf

[3] Ibidem, Presencia Suiza.

[4] Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión (2014). Ley Federal de Consulta Popular. Consultado en: http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LFCPo.pdf

[5] Departamento Federal de Asuntos Exteriores (DFAE), Presencia Suiza en colaboración con el INE (2018). Democracia Directa Moderna.

About the author

Natalia Villanueva has a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations with a concentration in International Business. She is particularly interested in issues like foreign trade, intellectual property, and finances.